About the exhibition

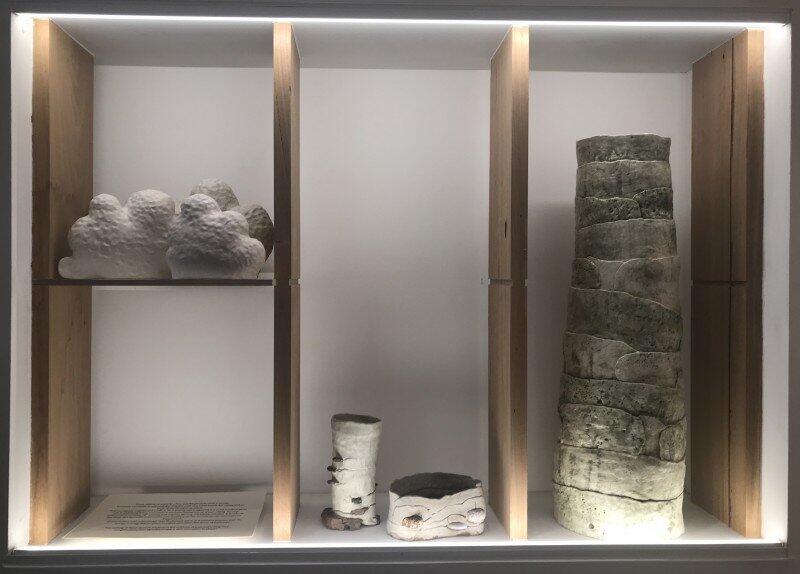

Conversations With a Landscape presents an investigation into my relationship with the Australian landscape and a particular rural place.

I have visited an area of the Victorian high country for many years. A body of work will be created using the pliant material of clay to capture a tangible sense of place. All works have been made at the site of investigation. The resulting vessels, record the textures and organic material of this place and my physical engagement with it.

These vessels and sculptures respond to a particular Mountain Gum, 712cm in diameter and thought to be pre-settlement. This tree has significant agency. It grows on the unceded land of the Taungurung people. It stands unharvested, majestic, and sublime on the edge of the Delatite River. A survivor of the colonial impact of sawmilling, the high-country cattle industry, the 19th century and ongoing farming and thriving leisure industry. It stands as a provocation and reminder of the longevity and pre-recorded history of this place.

This exhibition proposes that we occupy a newly redefined place in nature, one that is observant and respectful. The objects made through this investigation explore a way of constructing and acknowledging landscape outside of colonial tropes and actions of consumption, ownership, and labelling.

These objects respond to a tree and the place in which it grows. The artist would like to acknowledge that this work was made beside the waters and on the lands of the Taungurung Clans.

This tree stands majestic and sublime, its imposing size suggesting it is many hundred years old. A vital living thing, a survivor of the colonialising impact of sawmilling, the high-country cattle industry,19th century, and ongoing farming and leisure activities. It stands on the verge of a stone-filled mountain river, teetering on the boundaries of possessed and Crown lands.

Conversations with a Landscape uses the framed space of a vitrine to propose that we occupy a newly defined place in nature and within the genre of landscape.

Robyn Phelan

Advice from the Clouds, ceramic sculptures of cumulus clouds, seemingly redolent of rain despite their vitreous materiality. These sculptures are made slowly, as clay is urged into hollow forms using coiling and pinching in relationship with time and the dryness of the air. The firmness of the sculpture is achieved by the evaporation of moisture from the clay. This is the inverse behaviour of how atmospheric clouds are formed by the massing of condensed water vapours. Clouds have a fleeting presence, whilst ceramic sculpture is permanent.

Nineteenth-century landscape features big, cloud-filled skies, whether they be tranquil sublime pastoral scenes or depictions of nature’s awe-inspiring elements. My inclusion of cloud sculptures is a deliberate Romantic gesture. British Romantic painter, John Constable devoted much of his landscape compositional picture plane to awe-inspiring climatic effects of the sky, in particular clouds. I too, am inspired by sublime summer skies. The sublime in Western art terms is understood to mean a quality of greatness or grandeur that inspires awe, wonder, provoking and inspiring emotional responses for artists and writers, particularly in relation to the natural landscape.

My sense of awe when gazing at Merrijig’s cloud-laden skies is filled with conflicting emotions. This beautiful place is a retreat from the city’s intensity and pollution. Yet, my eco-anxiety bleeds through this tranquility for in this natural environment my eyes search skyward for hints of smoke and my eyes focus downwards to my smartphone, checking virtual weather and bushfire alerts and warnings, both indicators of sublimely terrifying or sublimely beautiful weather.

Robyn Phelan